In April 2017, Dame Linda Dobbs was appointed to review whether Lloyds Banking Group had covered up a £1 billion scandal at HBOS, the lender it had rescued in 2009. The former High Court judge expected the exercise to be finished in a “matter of months”. She was wrong.

More than seven years on, there’s still no sign of it and, as the Dobbs review threatens to rival some of the slowest official reports in British history, there are accusations that it risks compounding the original alleged cover-up.

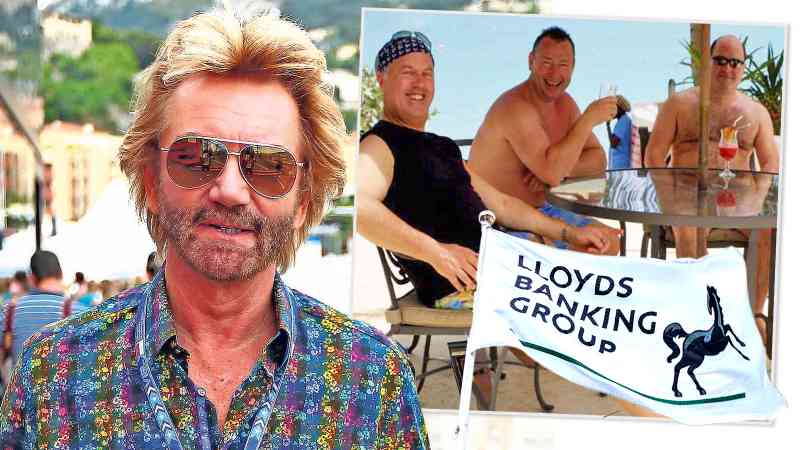

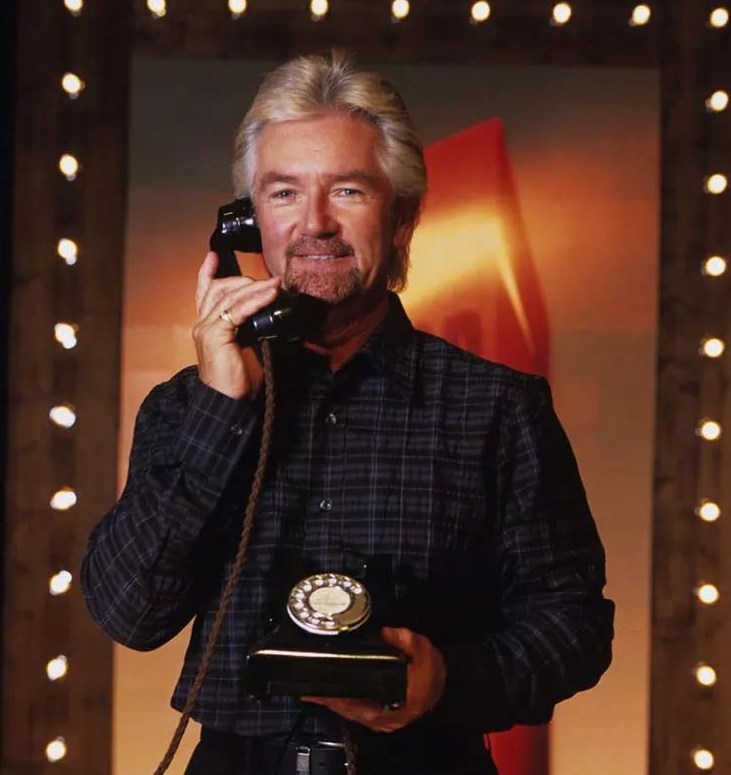

Noel Edmonds, the media personality whose Unique Group was caught up in the affair Dobbs is investigating, fears that her review might even surpass the notoriously protracted Edinburgh Tram inquiry. That investigation of a botched infrastructure project took nearly nine years to be completed and was said to have turned into a “bigger scandal than the one it was set up to look into”.

According to Edmonds, Dobbs, 73, is becoming similarly contentious. “When the upper echelons of the UK regime suspect they’ll be held accountable, their weapon of choice is a time-consuming inquiry from which ‘lessons will be learnt’. History suggests this is a very effective way of protecting the interests of the elite,” he said.

The review relates to Lloyds’ response to a fraud linked to the Reading branch of HBOS. Bankers and business consultants exploited reckless credit policies to steal from HBOS, with Lynden Scourfield, a banker, arranging for customers to appoint and pay fees to third-party consultants from a group called Quayside Corporate Services as a condition of continued bank support.

Quayside took control of small companies and produced “turnaround plans” to secure, and ultimately to steal, debt and fees from the bank and assets from customers, many of which were forced into insolvency. Scourfield received gifts, including cash, holidays and sex with prostitutes, while David Mills, the ringleader of Quayside, bought a 100ft yacht. The scam was said to be worth £245 million when cases came to court, but an internal review commissioned by Lloyds has put the true cost at closer to £1 billion.

HBOS, and later Lloyds, pursued surviving companies for associated debts after senior executives discovered the scam in early 2007. Scores of small and medium-sized businesses were wrecked and hundreds more were caught up in the fallout. Six people were jailed in January 2017, with Judge Martin Beddoe concluding that the affair had left people “cheated, defeated and penniless”.

The time served by some of the perpetrators has been shorter than the Dobbs review, which is looking into claims that Lloyds covered up the scam, frustrated the police investigation and added to the suffering of victims. The bank has dropped its resistance to the idea that victims were damaged by Quayside and has set up contentious compensation schemes.

A senior banking source familiar with the discovery of the fraud in 2007 claimed that the “HBOS corporate board knew there was a situation at Reading from early 2007, so Lloyds must have known quite quickly and certainly by the time the takeover was going through. Instead of owning up and redressing the issue, they decided the best option was to further destroy businesses hoping that would get rid of the problem. It seems quite clear-cut to me. These reviews take time, but I am surprised at how long this one is taking.”

At the end of last year, Paul and Nikki Turner, the owners of Zenith, a music publishing business ruined by Quayside, wrote to Adam Wiseman KC, counsel to the review, to express their concerns. “It is clearly in Lloyds Banking Group’s interest for the facts never to come out, despite the wealth of documentation the review already has received, which unequivocally evidences what Lloyds knew about HBOS Reading, when it knew it and what it did about it,” they wrote. “Are Nikki and I to conclude we totally misplaced our faith and trust in the integrity of this review?”

In the exchange, seen by The Times, Dobbs replied in January: “Your confidence in the integrity of the review is not misplaced. I promised a “no stone unturned” approach and that continues to be the objective.” More than six months on, her review is still accepting new information.

Dobbs told The Times: “I am deeply sympathetic to the concerns of the victims. I appreciate that, even before I was appointed, many feel that they had already waited too long for their voices to be heard. Where serious allegations have been raised about the adequacy of past investigations, I owe it to those victims to conduct a comprehensive inquiry and reach robust conclusions. That means no short cuts.”

Lloyds is paying for the exercise, which at one point had more than 50 barristers working on it. The bank won’t say how much it is costing. It has taken a combined £1.3 billion of charges related to the affair overall, including the costs of compensation schemes and the review (but not counting original losses from the scam).

Mark Brown, the general secretary at BTU, the biggest independent trade union for Lloyds’ staff, said he feared the bank may be “content to spend the millions this must be costing to see it kicked into the long grass”.

The inquiry is seeking to establish the facts about what was known and what ought to have been known and is analysing the conduct of both the bank as a corporate entity and of individuals working for it and acting on its behalf. It has taken oral or written evidence from a substantial number of witnesses and has considered hundreds of thousands of documents covering a period spanning almost two decades. Unusually, it has considered documents covered by legal professional privilege (confidential correspondence between lawyer and client involving legal advice). The process for handling these documents is said to be complex and time-consuming. Interviews and evidence-gathering are almost complete and drafting of the review has begun, although a significant amount of analysis is outstanding.

In 2020, having interviewed many victim and police witnesses, Dobbs said the “final stage” of the review would comprise interviews with Lloyds’ executives and staff and that she had hoped to complete them that autumn. As a non-statutory review, Dobbs cannot compel witnesses to be interviewed. This has been cited as a significant delaying factor because the review has been forced to work around witness availability, while the process for taking written evidence is said to be extremely time-consuming.

Brown proposed that Dobbs write to Charlie Nunn, Lloyds’ chief executive, and should “say who is holding up her work. These people will have share options and the bank should be able to encourage them to speak.”

Dobbs said: “Given the challenges of a non-statutory investigation, this unfortunately must take more time than they or I would like. We are working hard to complete the substantial work still required so that I can deliver my report.”

A victim of the scandal who has provided evidence to the review but who asked not to be named questioned why Dobbs had not published an interim summary. “Dobbs must know the direction of travel. If people were complicit in covering it up, she could say she has seen evidence of this, without naming them pending more work.”

The Turners, who like Edmonds received compensation from Lloyds, claimed that they had provided “hundreds of thousands of documents which show Lloyds covered it up. There are only so many times of being told to keep the faith and trust in her review before those words become a meaningless echo and, after over seven years, the echo is hollow and petering out.”

A Lloyds spokesman said that the bank could not comment on an independent investigation but would “continue to provide every assistance the review requires. We remain extremely sorry and have publicly apologised to all the customers who were impacted for the time it has taken to compensate them. Our intention has always been, and remains, to provide fair and generous compensation.”

The bank has said it will make the findings available to MPs on the Commons’ Treasury select committee when the report is finally produced.